Oh You ve Got to Fall in Love Again

| "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Side A of the US single | ||||

| Single by The Righteous Brothers | ||||

| from the album Yous've Lost That Lovin' Feelin' | ||||

| B-side | "There'south a Woman" | |||

| Released | Nov 1964 | |||

| Recorded | Oct 1964[i] | |||

| Studio | Gold Star, Hollywood | |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length | 3:45 | |||

| Label | Philles | |||

| Songwriter(s) |

| |||

| Producer(s) | Phil Spector | |||

| The Righteous Brothers singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

"Y'all've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" is a song by Phil Spector, Barry Isle of mann and Cynthia Weil, first recorded in 1964 past the American song duo the Righteous Brothers, whose version was as well produced by Spector and is cited by some music critics as the ultimate expression and illustration of his Wall of Audio recording technique.[ii] The record was a critical and commercial success on its release, reaching number ane in early February 1965 in both the United States and the United Kingdom. The unmarried ranked No. 5 in Billboard's twelvemonth-end Top 100 of 1965 Hot 100 hits – based on combined airplay and sales, and not including 3 charted weeks in December 1964 – and has entered the United kingdom Meridian Ten on an unprecedented three occasions.[three]

"Yous've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" has been covered successfully by numerous artists. In 1965, Cilla Blackness's recording reached No. 2 in the UK Singles Nautical chart. Dionne Warwick took her version to No. 16 on the Billboard Hot 100 nautical chart in 1969. A 1971 duet version past singers Roberta Flack and Donny Hathaway peaked at No. 30 on the Billboard R&B singles nautical chart. Long John Baldry charted at No. 2 in Australia with his 1979 remake and a 1980 version by Hall and Oates reached No. 12 on the United states Hot 100.

Various music writers have described the Righteous Brothers version as "ane of the best records ever made" and "the ultimate pop record".[1] In 1999 the performing-rights organization Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI) ranked the song every bit the most-played song on American radio and television set in the 20th century, having accumulated more than eight 1000000 airplays by 1999,[4] and almost 15 one thousand thousand by 2011.[5] It held the stardom of being the most-played song for 22 years until 2019, when information technology was overtaken by "Every Jiff Yous Take".[6] In 2001 the song was chosen every bit one of the Songs of the Century past RIAA, and in 2003 the track ranked No. 34 on the listing of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time by Rolling Rock. In 2015 the single was inducted into the National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[vii]

Groundwork and composition [edit]

In 1964, music producer Phil Spector conducted the band at a show in San Francisco where the Righteous Brothers was as well appearing, and he was impressed plenty with the duo to want them to record for his own label, Philles Records.[viii] All the songs previously produced by Spector for Philles Records featured African-American singers, and the Righteous Brothers would be his first white song human activity. Withal, they had a song manner, termed blue-eyed soul, that suited Spector.[9]

Spector commissioned Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil to write a song for them, bringing them over from New York to Los Angeles to stay at the Chateau Marmont and so they could write the song.[1] Taking a cue from "Baby I Need Your Loving" by The Four Tops, which was then ascension in the charts, Isle of man and Weil decided to write a ballad.[10] Mann wrote the melody first, and came up with the opening line, "You never shut your eyes anymore when I buss your lips", influenced by a line from the vocal "I Love How You Love Me" that was co-written by Mann and produced by Spector – "I dearest how your eyes shut whenever you osculation me".[11] [12] Isle of man and Weil wrote the first ii verses quickly, including the chorus line "y'all've lost that lovin' feelin'". When Spector joined in with the writing, he added "gone, gone, gone, whoa, whoa, whoa" to the end of the chorus, which Weil disliked.[12] [13] The line "you've lost that lovin' feelin'" was originally just intended to be a dummy line that would be replaced later, but Spector liked it and decided to go along it.[1] The form of the song is of verse-chorus-poesy-chorus-span-chorus or ABABCB course.[14] Mann and Weil had issues writing the span and the ending, and asked Spector for help. Spector experimented on the piano with a "Hang On Sloopy" riff that they then congenital on for the bridge.[12]

Weil recalled that, "after Phil, Barry and I finished [writing it], we took it over to the Righteous Brothers. Bill Medley, who has the low voice, seemed to like the song."[xv] However, Medley initially felt that the song did non suit their more uptempo rhythm and blues way, and Mann and Spector had sung the song in a college central: "And we just idea, 'Wow, what a good song for The Everly Brothers.' But it didn't seem right for the states."[16] [17] The song, which has a very big range, was originally written in the college key of F. But to accommodate Medley's baritone voice, the key was gradually lowered to C ♯ in the recording,[eighteen] which, together with slowing the song downward, changed the "whole vibe of the song", according to Medley.[17] [19]

Bobby Hatfield reportedly expressed his badgerer to Spector when he learned that Medley would start the first verse alone and that he had to wait until the chorus before joining in. Prior to this, they would have been given equal prominence in a song. When Hatfield asked Spector but what he was supposed to do during Medley'due south solo, Spector replied, "You tin go directly to the bank!"[15] [20]

The Righteous Brothers recording [edit]

The song was recorded at Studio A of Gold Star Studios in Los Angeles.[21] When Hatfield and Medley went to record the vocals a few weeks after the vocal was written, all the instrumental tracks had already been recorded and overdubbed.[12] They recorded the vocal many times – Medley sang the opening verse over and over again until Spector was satisfied, and the procedure was then repeated with the side by side verse. The recording took over 39 takes and around eight hours over a period of two days.[1] [12]

The vocal would go ane of the foremost examples of Spector'south "Wall of Sound" technique. It features the studio musicians the Wrecking Coiffure; playing on this recording were Don Randi on piano, Tommy Tedesco on guitar, Carol Kaye and Ray Pohlman on bass, and Steve Douglas on sax.[22] They were besides joined by Barney Kessel on guitar and Earl Palmer on drums. Jack Nitzsche usually arranged the songs for Spector, simply he was absent, and the arrangement was done past Gene Page.[ix] [23] As with his other songs, Spector started by cutting the instrumental track first, building up layers of sound to create the Wall of Sound effect. The recording was done mono so Spector could fix the audio exactly every bit he wanted it.[21] According to sound engineer Larry Levine, they started recording four acoustic guitars; when that was gear up, they added the pianos, of which there were three; followed past iii basses; the horns (ii trumpets, two trombones, and three saxophones); then finally the drums.[21] The vocals by Hatfield and Medley were and so recorded and the strings overdubbed.[i] The background singers were mainly the song group The Blossoms, joined in the song's crescendo by a immature Cher.[24] Reverb was practical in the recording, and more than was added on the atomic number 82 vocals during the mix.[21] According to music writer Robert Palmer, the effect of the technique used was to create a sound that was "deliberately blurry, atmospheric, and of course huge; Wagnerian rock 'n' scroll with all the trimmings."[1]

The song started slowly in the recording, with Medley singing in a low baritone voice.[17] Correct before the second verse started, Spector wanted the tempo to stay the same, simply the vanquish to be just a fiddling behind where they are supposed to country to requite the impression of the song slowing down.[25] The recorded vocal was three ticks slower and a tone and a half lower than what Mann and Weil had written.[12] When Isle of mann heard the finished record over the phone, he thought that it had been mistakenly played at 33 ane/3 instead of 45 rpm and told Spector, "Phil, you have information technology on the wrong speed!"[15] [xviii]

Even with his involvement in the song, Medley had his doubts considering information technology was unusually long for a pop song at the time. In an interview with Rolling Stone mag, he recalled, "We had no idea if it would exist a striking. It was too dull, too long, and right in the middle of The Beatles and the British Invasion." The song ran for nigh iv minutes when released. This was as well long by contemporary AM radio standards; radio stations at that time rarely played songs longer than three minutes considering longer songs meant that fewer ads could be placed between song sets.[22] Spector, nevertheless, refused to shorten it. Following a proposition by Larry Levine,[21] Spector had "3:05" printed on the label, instead of the rails's actual running fourth dimension of three:45. He also added a false ending which fabricated the recording more dramatic, and also tricked radio DJs into thinking it was a shorter song.[15] [26]

The production of the single cost Spector around $35,000, then a considerable corporeality.[27] [28] Spector himself was securely concerned virtually the reception to a song that was unusual for its time, worrying that his vision would not be understood. He canvassed a few opinions – his publisher Don Kirshner suggested that the vocal should be re-titled "Bring Dorsum That Lovin' Feelin'", while New York DJ Murray the K idea that bass line in the middle department, similar to that of a slowed-downwardly "La Bamba", should be the beginning of the song. Spector took these as criticisms and later said: "I didn't sleep for a calendar week when that record came out. I was so sick, I got a spastic colon; I had an ulcer."[29]

Reception [edit]

Andrew Oldham, who was then the manager of the Rolling Stones and a fan and friend of Spector, chanced upon Spector listening to a examination pressing of the song that had but been delivered. Oldham later wrote, "The room was filled with this amazing audio, I had no thought what it was, but it was the about incredible affair I'd ever heard."[30] He added, "I'd never heard a recorded track so emotionally giving or empowering."[31] Later, when Cilla Black recorded a rival version of the same song and information technology was racing upward the British charts ahead of The Righteous Brothers' version, Oldham was appalled, and took information technology upon himself to run a full-folio advertizing in Melody Maker:

This advert is not for commercial gain, it is taken as something that must be said almost the not bad new PHIL SPECTOR Tape, THE RIGHTEOUS BROTHERS singing "You lot'VE LOST THAT LOVIN' FEELING". Already in the American Top Ten, this is Spector's greatest production, the terminal word in Tomorrow'due south sound Today, exposing the overall mediocrity of the Music Industry.

Signed,

Andrew Oldham[32]

In other ads, Oldham also coined a new term to depict the song, "Phil Spector'south Wall of Sound", which Spector after registered every bit a trademark.[32]

Assessments by music writers were also highly positive. Nick Logan and Bob Woffinden idea that the vocal might be "the ultimate pop record ... hither [Spector's] genius for production truly bloomed to create a unmarried of epic proportion ..."[1] Richard Williams, who wrote the 1972 biography of Phil Spector Out of His Caput, considered the song to be i of the best records ever made, while Charlie Gillett in his 1970 book The Sound of the City: The Rise of Rock and Coil wrote that "the ebb and menses of passion the record accomplished had no direct equivalent."[1] [33] Mick Dark-brown, author of a biography of Spector, Tearing Downwards the Wall of Sound, considered the vocal to be "Spector'due south defining moment" and his "most Wagnerian production yet - a funeral march to departed love".[29] The opening line was said to be "one of the most familiar opening passages in the history of pop",[34] and Vanity Fair described the song equally "the about erotic duet between men on record".[35] However, when it was first presented on the BBC idiot box panel show Juke Box Jury in January 1965 upon its release in the U.k., information technology was voted a miss by all four panelists, with i questioning if information technology was played at the correct speed.[36]

In that location were initially reservations about the song from the radio manufacture; a common complaint was that it was too long, and others also questioned the speed of the vocal, and thought that the singer "keeps yelling".[37] Some stations refused to play the song after checking its length, or after it had caused them to miss the news.[26] The radio industry trade publication Gavin Report offered the opinion that "blueish-eyed soul has gone besides far".[37] In Britain, Sam Costa, a DJ on the BBC Light Programme, said that The Righteous Brothers' record was a chant, calculation, "I wouldn't fifty-fifty play it in my toilet."[38] All the same, despite the initial reservations, the vocal would become highly pop on radio.[39]

Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys heard the song and rang Mann and Weil in Jan 1965 to say: "Your song is the greatest record always. I was ready to quit the music business, only this has inspired me to write once more."[12] Wilson later referred to the Beach Boys' 1966 vocal "Good Vibrations" as his effort to surpass "Y'all've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'".[twoscore] Over the subsequent decades, he recorded numerous unreleased renditions of "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'". One of them, recorded during the sessions for the 1977 album The Beach Boys Love Y'all, was released on the 2013 compilation Fabricated in California.[41]

Spector himself later rated the song as the meridian of his achievement at Philles Records.[42]

Commercial success [edit]

"Yous've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" debuted on the American national chart on Dec 12, 1964. It topped the Billboard Hot 100 on February half dozen, 1965, and remained there for another week; its 16-week run on the Hot 100 was unusually lengthy at that fourth dimension. And it was the longest recording to top the nautical chart up to that time.[43] In addition, the single crossed over to the R&B charts, peaking at No. 2.[44] Billboard ranked the tape every bit the No. 5 single of 1965.[45]

The single was released in the UK in January 1965, debuting at No. 35 in the nautical chart dated Jan 20, 1965. In its fourth week it reached number i, where it remained for ii weeks, replaced by the Kinks' "Tired of Waiting for You".[46] It would become the merely single to e'er enter the United kingdom Superlative Ten 3 times, existence re-released in 1969 (No. 10), and once more in 1990 (No. three). The 1990 re-release was issued as a double A-sided single with "Ebb Tide" and was a follow-upwardly to the re-release of "Unchained Melody", which had hit number one as a event of being featured in the blockbuster film Ghost. "Yous've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" too reached No. 42 later on a 1977 re-release and in 1988 reached No. 87.[46]

In Ireland, "You lot've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" charted twice, first in January 1965, when it peaked at No. ii,[47] and again in December 1990, following its reissue as a double A-sided single with "Ebb Tide", when information technology climbed to No. 2 once again. The original Righteous Brothers recording remains the only version of the vocal to nautical chart in Republic of ireland.[48] In the Netherlands "Y'all've Lost That Lovin' Feelin" reached No. 8 in March 1965, with three versions ranked together as one entry: those of the Righteous Brothers, Cilla Black (a UK No. 2) and Dutch singer Trea Dobbs (nl).[49]

Accolades [edit]

In 1965, the Righteous Brothers recording of "Yous've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" was nominated in the All-time Rock and Roll Recording category at the 7th Annual Grammy Awards.[50] It was also awarded Best Pop Single To Date 1965 in the Billboard Disc Jockey Poll.[51]

In 2001, this recording was ranked at No. 9 in the list of Songs of the Century released by the Recording Industry Clan of America and the National Endowment for the Arts.[52] In 2004, the aforementioned recording was ranked at No. 34 by Rolling Stone magazine in their list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Fourth dimension.[53] In 2005, "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" was awarded the Songwriters Hall of Fame's Towering Song Award presented to "the creators of an private vocal that has influenced the civilization in a unique way over many years".[54]

In 2015, the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress, which each yr selects from 130 years of sound recordings for special recognition and preservation, chose the Righteous Brothers rendition every bit one of the 25 recordings that have "cultural, creative and/or historical significance to American lodge and the nation's audio legacy".[7] [55]

Chart performance [edit]

Weekly charts [edit]

Certifications [edit]

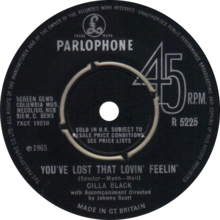

Cilla Blackness version [edit]

| "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

One of side-A labels of United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland single | ||||

| Single by Cilla Blackness | ||||

| from the anthology Is It Love? | ||||

| B-side | "Is It Honey" | |||

| Released | January 1965 | |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length | three:09 | |||

| Characterization | Parlophone | |||

| Songwriter(due south) |

| |||

| Producer(due south) | George Martin | |||

| Cilla Blackness singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

Background [edit]

English vocaliser Cilla Black first became a recording star by roofing Dionne Warwick's newly released American hit "Anyone Who Had a Heart" for the UK market place, which gave her a number one vocal in both the Uk Singles Chart and the Irish Singles Chart in February 1964, out-performing Dionne Warwick'southward original version, which simply peaked at No. 42 in the UK. Black's producer George Martin repeated this strategy with the Righteous Brothers "Yous've Lost That Lovin' Feeling" that had just been released in the Us. Black'south version is shorter with an abbreviated bridge, which she explained past saying: "I don't want people to go bored".[69] The abbreviation also removed the necessity of Black'southward attempting to match the Righteous Brothers' climactic vocal trade-off.

Nautical chart rivalry [edit]

Both Cilla Black's and the Righteous Brothers versions of the vocal debuted on the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland chart in the same week in January 1965, with Black debuting higher at No. 28.[70] According to Tony Hall of Decca Records who was responsible for promoting the Righteous Brothers tape in the UK, Black's version was preferred by BBC radio where i of its DJs disparaged the Righteous Brothers' version every bit a "dirge" and refused to play it. Hall therefore requested that Spector ship the Righteous Brothers over to United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland to promote the song and so information technology might accept a chance on the chart.[38] [42]

The following week Black remained in ascendancy at No. 12 with the Righteous Brothers at No. xx. The Righteous Brothers came over to United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, spent a week promoting the song and performed for television shows in Manchester and Birmingham.[38] At the same fourth dimension, Andrew Oldham placed a full-folio ad on Tune Maker promoting the Righteous Brothers version at his own initiative and expense, and urged the readers to spotter the Righteous Brothers appearance on the ITV television evidence Gear up Steady Get! [42] In its third week on the Feb 3, 1965 nautical chart, Blackness jumped to No. two, while the Righteous Brothers fabricated an even larger jump to No. iii. Hall recalled meeting at a party Brian Epstein, the manager of Black, who said that Black'southward version would be number one and told Hall, "You haven't a promise in hell."[42]

However, in its fourth week, Black'due south version began its descent, dropping to No. 5, while the Righteous Brothers climbed to number i.[seventy] Cilla Blackness then reportedly cabled her congratulations to the Righteous Brothers on their reaching number one.[42] Black'due south version of "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" would prove to be her highest charting Uk single apart from her two number ones: "Anyone Who Had a Middle" and "You lot're My Globe". While Black's version was released in Republic of ireland, it did not make the official Irish gaelic Singles Nautical chart as published by RTÉ, but it reached No. 5 on the unofficial Evening Herald charts.[ citation needed ]

Black remade "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" for her 1985 Surprisingly Cilla anthology.

Chart performance [edit]

Weekly charts [edit]

| Chart (1965) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Commonwealth of australia Go-Set [71] | 15 |

| UK Singles (OCC)[72] | ii |

| Holland (Muziek Expres) [73] | 9 |

Year-cease charts [edit]

| Chart (1965) | Rank |

|---|---|

| UK Singles Chartt[66] | 77 |

Dionne Warwick version [edit]

| "You've Lost That Lovin' Feeling" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Side A of US unmarried of Warwick'southward recording | ||||

| Single by Dionne Warwick | ||||

| from the anthology Soulful | ||||

| B-side | "Window Wishing" | |||

| Released | September 1969 | |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length | 3:02 | |||

| Label | Scepter | |||

| Songwriter(s) |

| |||

| Producer(s) |

| |||

| Dionne Warwick singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

Background [edit]

In 1969, American vocalizer Dionne Warwick recorded a cover version of "You've Lost That Lovin' Feeling" for her studio album Soulful. Her version was the only single released from the album and it was aimed to showcase Warwick every bit more of an R&B singer than was evidenced by her work with Burt Bacharach. Co-produced by Warwick and Chips Moman and recorded at American Sound Studios in Memphis, Tennessee, Soulful was one of Warwick's most successful albums peaking at No. 11 on the Billboard 200 album chart. The single "You've Lost That Lovin' Feeling" reached No. 16 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart, and charted at No. 13 on the Billboard R&B singles chart.[74] In Commonwealth of australia the Go-Set Superlative 40 chart ranked Warwick's version of "You lot've Lost That Lovin' Feeling" with a No. 34 peak in January 1970.[71] In Warwick's version of the song, she spells the terminal give-and-take of the title out fully as "feeling" rather than the usual "feelin'".

Chart performance [edit]

Weekly charts [edit]

| Nautical chart (1969–70) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australia Go-Set [71] | 34 |

| Canada Summit Singles (RPM)[75] | 12 |

| Canada Developed Gimmicky (RPM)[76] | 10 |

| US Billboard Hot 100[77] | sixteen |

| United states Adult Contemporary (Billboard)[78] | ten |

| The states Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs (Billboard)[79] | 13 |

| US Cash Box Top 100 | 14 |

Year-terminate charts [edit]

| (1969) | Rank |

|---|---|

| United states Billboard Hot 100[80] * | 132 |

(* - unofficial stratified ranking)

Roberta Flack and Donny Hathaway version [edit]

| "Y'all've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single by Roberta Flack and Donny Hathaway | ||||

| from the album Roberta Flack & Donny Hathaway | ||||

| B-side | "Exist Real Black for Me" | |||

| Released | September 25, 1971 | |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length | 3:52 | |||

| Label | Atlantic | |||

| Songwriter(s) |

| |||

| Producer(s) | Joel Dorn | |||

| Roberta Flack and Donny Hathaway singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

Groundwork [edit]

In 1971, American singers Roberta Flack and Donny Hathaway recorded a cover version of "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'". Their version of the song was produced by Joel Dorn and was included on their 1972 cocky-titled duet album Roberta Flack & Donny Hathaway, issued on the Atlantic Records label. Their version of the vocal was released equally the second single from the album after the Top thirty version of "Y'all've Got a Friend". The Flack/Hathaway take on "Y'all've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" reached No. thirty on the Billboard R&B singles chart and charted at No. 71 on the Billboard Hot 100 pop chart. It also reached No. 57 in the Cash Box Top 100 Singles and peaked at No. 53 on the Record Globe 100 Popular Chart.[81]

Nautical chart performance [edit]

Weekly charts [edit]

| Chart (1971) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| US Billboard Hot 100[82] | 71 |

| The states Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs (Billboard)[83] | 30 |

| US Cashbox Top 100[84] | 57 |

Yr-cease charts [edit]

| Year-end chart (1971) | Rank |

|---|---|

| U.s.a. Billboard Hot 100[85] | 422 |

Long John Baldry version [edit]

| "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single by Long John Baldry & Kathi McDonald | ||||

| from the album Baldry'southward Out | ||||

| B-side | "Baldry's Out" | |||

| Released | 1979 | |||

| Genre | Stone | |||

| Length | 5:00 | |||

| Label | EMI Capitol | |||

| Songwriter(s) |

| |||

| Producer(s) | Jimmy Horowitz | |||

| Long John Baldry & Kathi McDonald singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

Groundwork [edit]

In 1979, English blues vocaliser Long John Baldry recorded a cover version of "You've Lost That Loving Feeling'" every bit a duet with Kathi McDonald for his album Baldry'southward Out, the Jimmy Horowitz-produced disc which was Baldry'due south first recording in his newly adopted homeland of Canada.[86] In this version, Kathi McDonald sang the latter half of the beginning poetry using the office from the second verse ("It makes me just experience similar crying ..."), inverting the usual order.

Released as a unmarried, Baldry's "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" charted at No. 45 on the Canadian RPM singles chart, and spilled over into the The states Billboard Hot 100 chart at No. 89. The single as well reached No. 2 in Australia in 1980.[87] Pecker Medley of the Righteous Brothers told Baldry that he liked their remake of the song better than his ain.[88] Baldry had first recorded the song – as "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" – for his 1966 album Looking at Long John. The Baldry/McDonald duet version of "You've Lost That Loving Feeling" also reached No. 37 in New Zealand.

Charts [edit]

| Chart (1979–80) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australia (Kent Music Report)[87] | 2 |

| Canada Top Singles (RPM)[89] | 45 |

| New Zealand (Recorded Music NZ)[90] | 37 |

| Us Billboard Hot 100[91] | 89 |

Hall & Oates version [edit]

| "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Australian single of Hall & Oates's recording | ||||

| Unmarried by Hall & Oates | ||||

| from the album Voices | ||||

| B-side |

| |||

| Released | September 27, 1980 | |||

| Recorded | Early 1980 | |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length |

| |||

| Label | RCA | |||

| Songwriter(southward) |

| |||

| Producer(s) | Daryl Hall & John Oates | |||

| Hall & Oates singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "Y'all've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" on YouTube | ||||

| Culling release | ||||

New Zealand single | ||||

Groundwork [edit]

In 1980, the American musical duo Hall & Oates recorded a cover version of "Yous've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" for their ninth studio album Voices. Their version of the song was produced by the duo and included a sparse organization contrasting with the lavish Righteous Brothers original version. It was the 2d non-original vocal Hall & Oates had always recorded. Co-ordinate to Oates, this was the terminal vocal recorded for the anthology, as information technology had been deemed complete with the other ten tracks. However, Hall and Oates felt that in that location was "something missing" from the album. Then they came across the Righteous Brothers' version of the song on a jukebox automobile while going out to get food and they decided to cover it. They went back to the studio, cutting it in a flow of iv hours, and placed on the album.[92]

The track was issued on RCA Records as the album's second single subsequently the original "How Does Information technology Feel to Exist Back" peaked at No. 30 on the Billboard Hot 100. The November peak of No. 12 on the Hot 100 chart fabricated "Yous've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" the first Hall & Oates single to ascend higher than No. 18 since the number one striking "Rich Daughter" in the spring of 1977.[93] [94] "Y'all've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" too reached No. 15 on the Billboard Developed Contemporary nautical chart, on the Radio & Records Airplay chart the vocal debuted at No. 30 on the September 26, 1980 issue, later vii weeks information technology reached and peaked at No. 4 staying at that place for one week, the song stayed on the tiptop 10 of the chart for half dozen weeks and remained on information technology for thirteen.[95] It also reached No. 55 in the UK Singles Chart.

Chart performance [edit]

Weekly charts [edit]

| Chart (1980–81) | Summit position |

|---|---|

| Canada Meridian Singles (RPM)[96] | 96 |

| Canada Adult Contemporary (RPM)[97] | 10 |

| UK Singles (OCC)[98] | 55 |

| United states of america Billboard Hot 100[99] | 12 |

| US Radio & Records CHR/Pop Airplay Chart[100] | 4 |

| US Adult Contemporary (Billboard)[101] | 15 |

Yr-end charts [edit]

| Nautical chart (1981) | Rank |

|---|---|

| Us Billboard Hot 100[102] | 90 |

Other versions [edit]

- 1965 – Joan Baez with Phil Spector on pianoforte, at The Big T.N.T. Show [103]

- 1968 – Nancy Sinatra with Lee Hazlewood on the album Nancy & Lee.[104]

- 1970 – Elvis Presley on the anthology That'south the Style It Is [105]

- 1975 – "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" charted C&W at No. 41 for Barbara Fairchild in 1975.[106]

- 1975 - The song was covered by Telly Savalas as a follow-up to his No. 1 single "If". Information technology reached No. 47 in the UK charts.[107]

- 1979 - The Human League created a synth-popular version on their kickoff album Reproduction.[108]

- 1986 – A remake of "Y'all've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" past Grant & Forsyth (formerly of Guys 'n' Dolls) reached no. 48 in the Netherlands.[109]

- 1988 – Carroll Baker took the song to No. 7 on the Country Singles chart in Canada.[110]

- 1996 – Günther Neefs reached No. 31 on the Belgian charts (Flemish region) with his 1996 recording "You've Lost That Lovin' Feeling".[111]

- 2002 – The song charted at No. 57 in Netherlands in 2002 for André Hazes & Johnny Logan.[112]

Popularity [edit]

The vocal is highly popular on the radio; co-ordinate to the performing-rights organization Circulate Music, Inc. (BMI), it became the nigh-played song of all time on American radio in 1997 with over 7 million airplays (all versions), overtaking the Beatles' "Yesterday".[39] At the cease of 1999, the song was ranked by the BMI as the virtually-played song of the 20th century, having been circulate more than 8 million times on American radio and television receiver,[4] and it remains the most-played song, having accumulated almost xv meg airplays in the U.s.a. past 2011.[5] The song likewise received 11 BMI Pop Awards by 1997, the most for any song,[113] and has received 14 in total so far.[114] In 2019, "Every Breath Yous Have" by The Police displaced it as the about played vocal on US radio.[half dozen]

The popularity of the song also means that it is one of the highest grossing songs for its copyright holders. It was estimated by the BBC programme The Richest Songs in the Earth in 2012 to be the tertiary biggest earner of royalties of all songs, backside "White Christmas" and "Happy Birthday to You".[115] [116] [117]

One reason for the song's resurgence during the mid-1980s was the vocal's inclusion in the iconic '80s movie Top Gun. After Bohemian (assisted by Goose) serenades his love interest with the tune, she returns the favor by selecting it on the jukebox at his old hangout to catch his attention and reunite. Equally the end credits begin to roll, the primary grapheme, Maverick, literally flies off into the sunset as the Righteous Brothers harmonic chorus continues in the background.

The vocal also made a meaning appearance in the Telly sitcom Thank you. Information technology was said to be the favorite song of main graphic symbol Rebecca Howe (Kirstie Alley) in the episode "Delight Mr. Postman" and was included in multiple episodes throughout the series.

The song has been adopted as a terrace chant by supporters of English football lodge Nottingham Forest. On 14 September 2013, Bill Medley visited Woods's City Footing to meet supporters before a match against Barnsley.[118]

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d e f k h i j Sullivan, Steve (October 4, 2013). Encyclopedia of Cracking Pop Vocal Recordings, Volume 2. Scarecrow Press. pp. 101–103. ISBN978-0810882959. Archived from the original on May 12, 2016. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ Dowling, Stephen. "Brothers in good company with hits". BBC.

- ^ "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'". Song Facts. Archived from the original on November 26, 2007. Retrieved November xvi, 2015.

- ^ a b "News | BMI Announces Meridian 100 Songs of the Century". BMI.com. December 13, 1999. Archived from the original on June 2, 2012. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ^ a b "Van's Brown Eyed Girl hits the 10 1000000 mark in U.s.". BBC. Oct five, 2011. Archived from the original on October 27, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ a b "BMI Announces Superlative Honors for its 67th Almanac Pop Awards" Archived November 6, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. BMI. Retrieved ix June 2019

- ^ a b "New Entries to National Recording Registry | News Releases - Library of Congress". Loc.gov. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved Oct thirteen, 2015.

- ^ Mednick, Avram (June 12, 2000). The 100 Greatest Rock 'n' Roll Songs Ever. iUniverse. p. 201. ISBN978-0595093045. Archived from the original on May xx, 2016. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ a b Williams, Richard (November 17, 2009). Phil Spector: Out Of His Head (Revised ed.). Passenger vehicle Press. ISBN9780857120564.

- ^ Brown, Mick (April 7, 2008). Tearing Down The Wall of Sound: The Rising And Autumn of Phil Spector. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 171. ISBN978-0747572473.

- ^ "Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil still have that lovin' feelin'". CBS. February 8, 2015. Archived from the original on November 24, 2015. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f yard Myers, Marc (July 12, 2012). "The Vocal That Conquered Radio". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November xiii, 2017. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ Larson, Sarah (November 26, 2013). "Mann and Weil on Broadway". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on November 25, 2015. Retrieved Nov 10, 2015.

- ^ Friedman, Sidney (2007). "In the Heart of the Music" lecture notes

- ^ a b c d Hinckley, David (1991). "Dorsum To Mono (Songs)". Archived from the original on November 24, 2015. Retrieved November 24, 2015. Notes from Phil Spector: Back to Mono (1958-1969) boxed-set booklet, see the recording details for the song

- ^ "Neb Medley of The subsequently Righteous Brothers". Songfacts. Archived from the original on October xviii, 2015. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ^ a b c ""Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" 1964-1965". The Pop History of Dig. Archived from the original on Oct 3, 2015. Retrieved Nov 11, 2015.

- ^ a b Moore, Rick (August eleven, 2014). "Lyric Of The Week: The Righteous Brothers, "You've Lost That Lovin' Feeling"". American Songwriter. Archived from the original on February 6, 2015.

- ^ Abrupt, Ken. "Soul & Inspiration: A Chat with Bill Medley of the Righteous Brothers". Rockcellar Magazine. Archived from the original on June 8, 2017. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time : 65 - Phil Spector, 'Back to Mono (1958-1969)'". Rolling Stone. May 31, 2009. Archived from the original on September 19, 2017. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Daley, Dan (March i, 2002). "Classic Tracks: The Righteous Brothers' "You've Lost That Lovin' Feeling"". Mix. Archived from the original on Nov 17, 2015. Retrieved Nov 10, 2015.

- ^ a b Don Randi, Karen "Nish" Nishimura (August 1, 2015). You lot've Heard These Easily: From the Wall of Sound to the Wrecking Coiffure and Other Incredible Stories. Hal Leonard. ISBN978-1495008825. Archived from the original on May 12, 2016. Retrieved Dec eighteen, 2015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Perrone, Pierre (October 23, 2011). "Obituary: Gene Page". The Independent. Archived from the original on April 8, 2019. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- ^ Greenfield, Robert (November 6, 2012). The Concluding Sultan: The Life and Times of Ahmet Ertegun. Simon & Schuster; Reprint edition. p. 165. ISBN978-1416558408. Archived from the original on April 25, 2016. Retrieved November 28, 2015.

- ^ Williams, Richard (November 17, 2009). Phil Spector: Out Of His Head (Revised ed.). Double-decker Press. ISBN9780857120564. Archived from the original on June 29, 2016. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ^ a b Williams, Richard (Nov 17, 2009). Phil Spector: Out Of His Head (Revised ed.). Motorcoach Press. ISBN9780857120564. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved Nov eleven, 2015.

- ^ Brown, Mick (Apr 7, 2008). Vehement Down The Wall of Sound: The Rise And Fall of Phil Spector. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 400. ISBN978-0747572473. Archived from the original on May 19, 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ^ Adams, James (February 5, 2003). "'I'm my ain worst enemy'". Globe and Mail service. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- ^ a b Brown1, Mick (February 4, 2003). "Popular's lost genius". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on September ten, 2018. Retrieved April four, 2018.

- ^ Thompson, Dave (April 7, 2008). Phil Spector: Wall of Hurting. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN9780747572473. Archived from the original on Apr 25, 2016. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ^ Andrew Loog Oldham (September 4, 2003). 2Stoned. Vintage. pp. 76–77. ISBN9780099443650. Archived from the original on May 2, 2016. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ^ a b Ribowsky, Marker (2000). He's A Insubordinate: Phil Spector, Stone and Roll's Legendary Producer . Cooper Square Press. pp. 186–187. ISBN9780815410447.

- ^ Gillett, Charlie (1970). The Sound of the Metropolis: Ascension of Stone and Coil. p. 227. ISBN9780285626195.

- ^ "Bobby Hatfield". The Daily Telegraph. November 7, 2003. Archived from the original on June 16, 2018. Retrieved Apr 4, 2018.

- ^ Grossberg, Josh (November half-dozen, 2003). "Righteous Bro Hatfield Dies". E Online. Archived from the original on December nine, 2015. Retrieved Dec 2, 2015.

- ^ Warner, Jay (2004). On this Day in Music History. Hal Leonard. p. 12. ISBN978-0634066931. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2015.

- ^ a b Dark-brown, Mick (April 7, 2008). Tearing Downward The Wall of Sound: The Rising And Autumn of Phil Spector. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 175. ISBN978-0747572473. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ^ a b c Leigh, Spencer (Nov vii, 2003). "Obituaries: Bobby Hatfield". The Independent. Archived from the original on June 23, 2018. Retrieved September xix, 2017.

- ^ a b Irv Lichtman (March 22, 1997). "'Lovin'' BMI'south Most-Performed Song". Billboard. Archived from the original on June 11, 2016. Retrieved November xxx, 2015.

- ^ Badman, Keith (2004). The Beach Boys, The Definitive Diary of America's Greatest Band on Stage and in the Studio . Backbeat Books. p. 117. ISBN0-87930-818-four.

- ^ "Beach Boys Producers Alan Boyd, Dennis Wolfe, Mark Linett Discuss 'Made in California' (Q&A)". Rock Cellar Magazine. September 4, 2013. Archived from the original on September xxx, 2013. Retrieved September 9, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Brown, Mick (April vii, 2008). Violent Downwards The Wall of Sound: The Rise And Fall of Phil Spector. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 176–177. ISBN978-0747572473. Archived from the original on May viii, 2016. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ^ Thompson, Dave (April 7, 2008). Phil Spector: Wall of Hurting. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN9780747572473. Archived from the original on May 10, 2016. Retrieved November xvi, 2015.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (2004). Top R&B/Hip-Hop Singles: 1942-2004. Record Enquiry. p. 492.

- ^ "Peak 10 Singles 1943-1983". Billboard. December 15, 1984. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved November ix, 2015.

- ^ a b "The Righteous Brothers". Official UK Charts Company. Archived from the original on November 28, 2015. Retrieved November 8, 2015. Click on Nautical chart Facts for complete charting information

- ^ "Billboard Magazine". February 27, 1965. Archived from the original on April 26, 2016. Retrieved Nov 8, 2015.

- ^ "Search the Charts". The Irish Charts - All there is to know. Archived from the original on June 3, 2009. Retrieved November xvi, 2015. Search Righteous Brothers for chart ranking

- ^ a b "calendar week 12 (20 maart 1965)". Media Markt 100. Archived from the original on December eight, 2015. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ^ "Grammy Awards 1965". Awards & Shows. Archived from the original on August 26, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2016.

- ^ Billboard. Apr iii, 1965. p. 39. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved January 3, 2016.

- ^ Allen, Jamie (March 8, 2001). "Songs of the Century' listing: The debate goes on". CNN. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved December 18, 2015.

- ^ "500 Greatest Songs of All Time". Rolling Stone. December eleven, 2003. Archived from the original on September 21, 2017. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- ^ "2005 Laurels & Induction Ceremony". Songwriter Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December xvi, 2015.

- ^ Lewis, Randy (March 25, 2015). "Library of Congress welcomes recordings by the Doors, Righteous Brothers". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ "Top RPM Singles: Issue 5612." RPM. Library and Athenaeum Canada.

- ^ "The Righteous Brothers – You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" (in High german). GfK Entertainment charts.

- ^ a b "The Irish gaelic Charts – Search Results – You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'". Irish Singles Chart.

- ^ a b c d "Righteous Brothers: Artist Chart History". Official Charts Company.

- ^ "The Righteous Brothers Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard.

- ^ "The Righteous Brothers – You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" (in Dutch). Ultratop 50.

- ^ "The Righteous Brothers – Yous've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" (in Dutch). Single Superlative 100.

- ^ "Official Singles Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company.

- ^ "The Righteous Brothers – Yous've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'". Tiptop xl Singles.

- ^ "Pinnacle 100 Hits of 1965/Superlative 100 Songs of 1965". Music Outfitter Inc. Archived from the original on March 31, 2016. Retrieved March xx, 2016.

- ^ a b "Peak 100 1965". UK charts Top Source Info. Archived from the original on Apr two, 2016. Retrieved April eight, 2016.

- ^ "Billboard Hot 100 60th Anniversary Interactive Chart". Billboard. Archived from the original on Baronial 3, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ^ "British unmarried certifications – Righteous Brothers – You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ Williams, Richard (2003). Phil Spector: out of his head. London: Jitney Printing. p. xc. ISBN0-7119-9864-7. Archived from the original on June x, 2016. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ a b "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'". Official UK Charts Company. Archived from the original on October 23, 2015. Retrieved November 8, 2015. Click on Chart Facts for complete charting information

- ^ a b c "10 Jan 1970: Singles". Become-Fix Charts. Archived from the original on August 29, 2016. Retrieved April eight, 2016.

- ^ "Cilla Black: Artist Nautical chart History". Official Charts Company.

- ^ "Dutch Muziek Expres Striking chart of 1965". Muziek Expres. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- ^ Warner, Jay (April 26, 2006). On this Day in Blackness Music History . Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 279. ISBN978-0634099267.

- ^ "Top RPM Singles: Result 8242." RPM. Library and Archives Canada.

- ^ "Elevation RPM Developed Contemporary: Outcome 8266." RPM. Library and Athenaeum Canada.

- ^ "Dionne Warwick Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard.

- ^ "Dionne Warwick Chart History (Adult Contemporary)". Billboard.

- ^ "Dionne Warwick Chart History (Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs)". Billboard.

- ^ "1969 Year End". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ "CASH BOX Top 100 Singles". Archived from the original on January 20, 2008.

- ^ "Roberta Flack & Donny Hathaway Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard.

- ^ "Roberta Flack & Donny Hathaway Chart History (Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs)". Billboard.

- ^ "CASH BOX TOP 100 SINGLES: Week catastrophe June 27, 1981". Cashbox Mag. Archived from the original on October 22, 2007.

- ^ "1971 Twelvemonth Cease". Bullfrogs Pond. Archived from the original on March 15, 2016. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ Cashmere, Paul (October v, 2012). "Kathi McDonald Dead At 64". Noise11. Archived from the original on June 17, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ^ a b Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (Illustrated ed.). St. Ives, Due north.S.Due west.: Australian Chart Book. p. 25. ISBN0-646-11917-6.

- ^ Myers, Paul (September 30, 2007). It Ain't Like shooting fish in a barrel: Long John Baldry and the Nascence of the British Blues . Greystone Books, Canada. p. 194. ISBN978-1553652007.

- ^ "Top RPM Singles: Issue 4549a." RPM. Library and Athenaeum Canada.

- ^ "Long John Baldry & Kathi McDonald – You've Lost That Loving Feeling". Pinnacle twoscore Singles.

- ^ "Long John Baldry Kathi MacDonald Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard.

- ^ Williams, Chris. "John Oates discusses 1980'south Voices by Hall and Oates". WaxPoetics. Archived from the original on September viii, 2018. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ^ Book, Ryan (December 12, 2014). ""You've Lost That Loving Feeling": 50 Years of The Righteous Brothers Archetype and Five Covers, from Elvis to Hall & Oates". The Music Times. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November sixteen, 2015.

- ^ "Daryl Hall & John Oates: Biography". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 21, 2015. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ^ "You lot've lost that lovin feeling (Hall + Oates)". Archived from the original on Feb ane, 2017. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ^ "Top RPM Singles: Issue 4701b." RPM. Library and Archives Canada.

- ^ "Top RPM Adult Contemporary: Issue 8266." RPM. Library and Archives Canada.

- ^ "Hall and Oates: Creative person Nautical chart History". Official Charts Visitor.

- ^ "Daryl Hall & John Oates Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard.

- ^ "Hall + Oates". Archived from the original on January 4, 2017. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ^ "Daryl Hall John Oates Chart History (Adult Contemporary)". Billboard.

- ^ "Acme 100 Hits of 1981/Top 100 Songs of 1981". Archived from the original on March vii, 2004. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ Thompson, Dave (2005). Phil Spector: Wall of Hurting. Sanctuary Publishing Ltd. ISBN978-1860746451. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved December twenty, 2015.

- ^ "Storybook Gilt: The 50th Anniversary of "Nancy & Lee"". Nancy Sinatra. February 27, 2018. Archived from the original on April 11, 2019. Retrieved Apr 11, 2019.

- ^ Marking Duffett (2018). Counting Downward Elvis: His 100 Finest Songs. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 136. ISBN978-1442248052. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved January xvi, 2019.

- ^ "Hot State Songs". Billboard. November one, 1975. Archived from the original on Baronial 15, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy equally championship (link) - ^ Olivia Bloechl; Melanie Lowe; Jeffrey Kallberg, eds. (2015). Rethinking Departure in Music Scholarship. Cambridge Academy Printing. p. 309. ISBN978-1107026674. Archived from the original on Oct 17, 2021. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ^ "Grant & Forsyth - You've Lost That Loving Feeling". Dutch Charts. Archived from the original on March thirteen, 2016. Retrieved December sixteen, 2015.

- ^ "Country Singles" (PDF). RPM. July 30, 1988. Archived (PDF) from the original on Nov 12, 2012. Retrieved March thirteen, 2016.

- ^ "Günther Neefs - You lot've Lost That Loving Feeling". Ultrapop. Archived from the original on March viii, 2018. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ "André Hazes & Johnny Logan - You lot've Lost That Loving Feeling". Dutch Charts. Archived from the original on February 29, 2016. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ For Sixth Year, Babyface wins BMI'southward Pinnacle Popular Trophy. Billboard. May 24, 1997. p. 109. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved January three, 2016.

- ^ "Barry & Cynthia's Bio". Barry Mann & Cynthia Weil. Archived from the original on December 30, 2015. Retrieved January 3, 2016.

- ^ "BBC4 ... The World's Richest Songs". Did You Watch Information technology. December 29, 2012. Archived from the original on Jan 1, 2016.

- ^ "The Richest Songs in the World". BBC. Archived from the original on January iv, 2016. Retrieved December 20, 2015.

- ^ Seale, Jack. "The Richest Songs in the Globe". Radio Times. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 20, 2015.

- ^ "Don't Lose That Loving Feeling - News - Nottingham Forest". www.nottinghamforest.co.uk. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

rutherfordtraturd.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/You%27ve_Lost_That_Lovin%27_Feelin%27

0 Response to "Oh You ve Got to Fall in Love Again"

Post a Comment